Gerald Beaulieu is a visual artist based in Stratford, PEI. He originally comes from Welland, Ontario. He studied art at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto where he graduated in 1987. Gerald has been awarded numerous Canada Council for the Arts awards and Prince Edward Island Council of the Arts awards. He has had over 70 solo and group exhibitions across Canada, the U.S. and Europe.

As a volunteer arts advocate, he has served on the boards of many local and national arts organizations. In these roles he has negotiated voluntary tariffs and collective agreements, presented at numerous conferences, nominated Governor General award winners, and successfully defended artists rights in the Supreme Court of Canada as the president of CARFAC National between 2006-2011.

You studied at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto in the late 80’s before moving to Prince Edward Island. It’s certainly a lot more difficult to make a career as an artist on P.E.I. than say Toronto. What drew you here?

The easy answer is a woman drew me here. When I was in Toronto it was becoming one of the more expensive places to live. I can see the career advantage of being in a cultural hub, but I’m a sculptor and I need space. You could buy cheap property back in the day for the price of a used car and I like to work late at night and use power tools so the lifestyle was just easier here. The economics of being an artist here are not that much different from living in a big city. You would obviously get more career opportunities in Montreal and Toronto but there are advantages and disadvantages to both.

You recently completed a digital residency with the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, the whole digital performance thing is a relatively new concept. How was that experience?

Because my work is so industrial, it was hard to do. Most people like to do a residency to get out of their studio. I have the better part of a hardware store in my studio, there’s 500 drill bits, 40 cans of paint and I’m used to just grabbing it off the shelf. So residences can kind of be like cooking in somebody else’s kitchen but there’s nothing in the pantry and all you have is a spoon and a spatula.

I heard you say that in your works the materials are often the metaphors. So with that in mind do you often come up with a concept for your works and then seek out materials that help fulfill that vision, or is it the other way around?

I usually think of the materials as metaphors directly. So if a material fits what I’m trying to convey in a work then I’ll just go source that. But it needs to meet the three requirements: Can I get it, Can I afford it, and do I have the technical expertise to use it; Because I like to do as much hands-on work as possible. I’m more of a material mercenary, I don’t have any devotion to any material, I’ll just use whatever I can get my hands on.

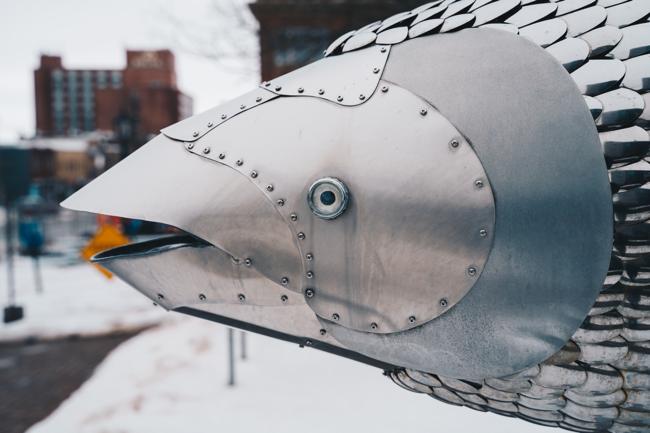

Sometimes I have a material I’m attracted to and I think about how to incorporate it into my work, other times I have an idea and that material will just suit that idea and it falls into place. So when I was making the crows I had the idea of roadkill, and I had the thought; What if I just made them really big and used the thing that killed them [tires] as the metaphor.

Your sculptures and works are often larger than life, I think back to the large lunar lander module you made several years ago for Art in the Open, or the giant crows you designed as part of the “Where The Rubber Meets the Road” series. Why go big? Does size dictate impact?

Size does dictate impact, but to me it’s more about the scale of things and I relate it to the scale of people. Since I’ve worked so much in architecture I think in those terms. The work kind of comes in three sizes now: a plant size, a vehicle size, and architectural size.

These works are quite substantive. It must take you a long time to plan out large works?

I think things through quite a bit before I dive in. Because as you go big the resources and the expenditures can be substantial and I don’t want to make a $5,000 dud. If you’re painting you could just paint over something you didn’t like. I like to think about my process quite a bit before I commit to it. Hopefully the theory actually translates when I actually do the experiment and do the work.

Are there any materials you’d like to work with but haven’t figured out how to work with yet?

I have some materials that are unfortunately impractical to use. I’d love to do a work that uses liquid mercury in lead trenches where it could just flow and move around. But unfortunately mercury evaporates into a toxic gas that’ll kill you. It would never pass any safety code. I’ve learned to give some ideas a lot of gestation time, just turning over and over in my mind. It’s kind of like marbles inside of a cage, they turn over and over and slowly fall out when the time is right.

It seems as though you create works that live in public spaces. Do you create pieces specifically with that in mind?

The thing is, It’s not art if nobody’s looking at it. To me, it’s all about engaging an audience in the way I do it, I don’t do it for therapy, you know, it’s a passion. It’s done to present to an audience the same way that I think most writers want people to read their books or like how musicians want to perform in front of an audience and have people listen and hear what they’re doing. Because without the feedback, it’s not gonna grow. That’s like making food that nobody else tastes. You can make something and it tastes great, but it’s much different than when you serve it to somebody, you see how they would react to it.

It’s difficult for a lot of artists to get their foot in the door, to get noticed, how do you suggest younger artists navigate that?

Sometimes you get your foot through the door and then realize the back door is a lot closer to the front door than you would’ve thought. Then you’re out the door pretty quick. But you’ve gotta find the next door to go in, and maybe you’re not in there for very long either. So you’re always searching for that next door, you’re always applying for the next job. So by all means it’s a gig-economy. If you can’t deal with rejection and adversity this is not the business for you, because you’re going to get it. There’s just no way to avoid it. I’ve had projects that I thought were bang on, but they didn’t fly. You have to keep in mind everyone else decides what you’re going to do sometimes, that is, if you submit something there’s a jury, there’s a selection committee so as an artist I can build it on my front lawn but sometimes that’s as far as I get in deciding what happens with it. It’s not like the economic fundamentals don’t apply to artists either. You have to have tough skin to survive in this business.

Do you think there’s a shortage of original ideas in the art world?

We’re in a very conservative time. I think there’s this real risk aversion to failure. Because failure can mean the end of it. For people that’s scary. Like imagine you get your big movie budget and have a colossal failure. You know, that would end you. Francis Ford Coppola did that with Apocalypse Now. He failed spectacularly at the box office, and that was the most expensive movie ever made. You develop this repertoire of work, and this is what you’re known for. And that’s what got you notoriety so it’s probably a challenge to kind of branch out completely on something else.

What does the future hold for you?

I’m moving on to a public art project for the town of Stratford for one of their parks. This will be the second insert done for the town. I’ve only been resident there for about seven years, so it’s nice to take part in.

Visit Gerald at:

Subscribe to our Newsletter

CreativePEI is funded in whole or in part by the Canada/Prince Edward Island Labour Market Agreements.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge that the land on which we operate is the traditional unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq Peoples. This territory is covered by the “Treaties of Peace and Friendship” which Mi’kmaq Peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725. The treaties did not deal with surrender of lands and resources but in fact recognized Mi’kmaq title and established the rules for what was to be an ongoing relationship between nations. We recognize that true reconciliation is an ongoing process. Acknowledging territory and First Peoples should take place within the larger context of genuine and ongoing work to forge real understanding, and to challenge the legacies of colonialism.